This site uses cookies to provide you with a great user experience. By using BondbloX, you accept our use of cookies.

Bond Market News

Greece – Letting Yields Slip

December 8, 2020

Greece 10Y bond yields recently hit an all-time low of 0.61%, breaking through the lows it hit in February (0.91%) before the Covid19 induced crisis. The country which was at the center of the Eurozone debt crisis and considered the riskiest debt in Europe over the last decade has made a spectacular comeback.

The country is rated Ba3/BB-/BB by Moody’s/S&P/Fitch. With yields dropping to an all-time low, they have inched closer to that of other advanced countries. This article aims to explain the falling Greek bond yields and to explore the factors that have aided it while analyzing other structural developments in the Greek bond markets.

A Look Into Debt To GDP Ratios

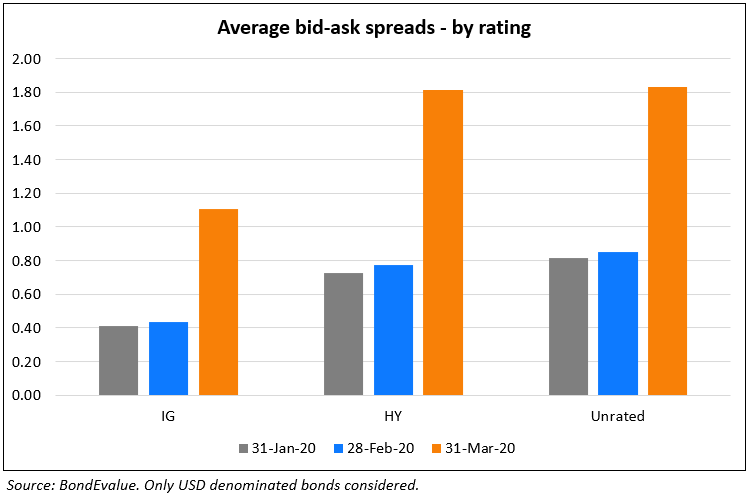

One of the important factors that can impact sovereign bond yields is the economy’s debt-to-GDP ratio. Economists find this ratio a very useful metric to compare the amount a country owes to its creditors as a percentage of the value of goods and services produced by the nation. In fact, the Eurozone has defined a reference value for the debt-to-GDP ratio through the Maastricht Treaty that requires the debt-to-GDP ratio to not exceed 60%. Despite that, many countries have breached this reference by a considerable margin. The table below illustrates the debt-to-GDP of Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain which are considered the “periphery” countries of the Eurozone (Germany, Belgium, Austria [mention a few more] are part the “core” countries). While Portugal and Spain had maintained their debt-to-GDP at or below 60% in in early 2000s after the EU was formed, Greece and Italy had debt-to-GDP closer to 100%. A sharp increase was observed in this metric after the financial crisis with debt-to-GDP ratios rising across the board. In 2019, Spain’s debt-to-GDP stood at ~95%, Portugal’s at ~117%, Italy at ~135% while the ratio for Greece was just short of 180%.

How Is Greece’s Debt Different?

To understand this better, we looked deeper into the type of debt of the four periphery countries. Like most countries, bonds and bills made up the large chunk of Italy, Portugal and Spain’s debt. However, that was not the case for Greece, which has the most bloated debt-to-GDP ratio.

Looking further into Greek debt (chart below) shows that its borrowings primarily are from the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), European Stability Mechanism (ESM) and Greek Loan Facility (GLF), three loan programs constituting ~67% of their debt while only ~19% is in the form of bonds and bills payable (37% in the table above is their bonds outstanding as a percentage of GDP). The three facilities from ‘official creditors’ were provided when Greece was reeling with its crisis for several years led by political chaos, accusations of fudging fiscal deficit numbers and resorting to austerity measures. The pie chart below shows the breakup of Greece’s debt holdings.

In 2012, the Eurozone had rolled out a second rescue package for Greece worth €130bn to avert a default with an aim to help Greece reduce its Debt to 120.5% of GDP by 2020. On the contrary, a leaked report of the Troika (the trio of the International Monetary Fund, European Union and European Central Bank) assessed that the fiscal outlook of Greece had deteriorated, which could lead to an increase in its debt-to GDP to 160% in 2020. Fast forwarding to today, there has been an increase to 177% and what was envisioned in 2012 by the Eurozone is yet to be achieved.

Why Are Greek Yields At Historical Lows?

Today, the Greek 10Y yields are at all-time lows. However, the question is if these are different from the rest of the Eurozone. A closer look at Greek yields suggests similarities to that of other periphery countries – Italy, Spain and Portugal which are also at all-time lows.

This has particularly happened on the expectations that the European Central Bank (ECB) will increase their asset purchases and surplus liquidity. However, what makes Greek yields stand out is the magnitude of the drop it has experienced over the last couple of years. Interestingly, Greek bonds were not a part of the ECB’s Asset Purchase Programme (APP) in 2015, while the debt of Italy, Portugal and Spain were all part of the APP. However, this trend has changed. During the ongoing pandemic, the ECB has been proactive in initiating steps to tackle the downturn. Most significantly, it embarked on a temporary Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) after the spike in yields across periphery countries in March due to Covid. This has led to a purchase of an increased amount of debt that includes government debt. Fortunately for Greece, its bonds were a beneficiary of the ECB program for the first time. The table below lists the ECB’s PEPP purchases across the four periphery countries.

Listed below are some reasons as to why Greek yields are at all-time lows:

- The ECB currently holds ~16.5% (€12.96bn) of Greece’s outstanding government bonds worth ~€78.6bn ($93bn) since Greece was included in the PEPP in March. This additional demand base has likely helped Greek bond yields go lower than the levels it hit in Feb (0.90%) post which Covid19 caused yields to spike ~3% in March.

- ECB had lifted restrictions on the limit imposed on Greek banks to hold sovereign bonds in March this year. Greek bonds have benefitted from the lifting of the sovereign bond holdings cap, which were imposed 5 years back as a part of the bailout package.

- Credit rating agencies also had good news for Greece. Moody’s recently upgraded Greece from B1 to Ba3 citing ongoing reforms – independent revenue administration resulting in higher tax revenues and improved compliance, government taking steps on non-performing exposures of banks and a new insolvency framework and other institutional steps. Moody’s also expects positive growth over the medium-term with EU recovery funds disbursement seeing Greece as the largest euro area beneficiary (€32bn/$38bn) relative to GDP (17% of 2019 GDP), providing significant support to both headline growth and investment. Greek 3Y bond yields went into ‘negative territory’ for the first time after the Moody’s upgrade.

- Another factor that has likely helped is the increased level of activity in markets measured by trading volumes where the ECB has acted like a backstop keeping yields low. The current year has seen record trading volumes of Greek 10Y bonds in the last 10 years, albeit significantly lower than the period before that. The table below shows the trading volumes of Greece’s 10Y bonds since 2011. It is seen that the volumes this year have been just short of double of the second highest issuance year (2014). In fact this year’s volumes alone have contributed to over 35% of Greek debt trading volumes in the entire decade.

It is worth noting that Greek yields had been falling and had hit a record low in Feb 2020 even before Covid struck. With the ECB’s several quantitative easing programmes leading to excess liquidity and depressed bond yields of core countries, investors started venturing into riskier sovereigns like the periphery nations like Italy, Spain etc. Further incremental liquidity, also saw investors take to Greeks bonds despite the sovereign not being part of the ECB QE programme then – a hunt for yield! “There’s a wall of money out there chasing these yields,” said Antoine Bouvet, a senior rates strategist at Dutch bank ING in February 2020. Bouvet also said investors were betting that the ECB would stick with sub-zero interest rates for an extended period adding to the appeal of markets like Greece and Italy that offer extra yield as compared to the Eurozone’s safest bonds. Besides, better growth also saw some expectations for a rating upgrade for Greece. This was vindicated when recently, despite the pandemic, Moody’s upgraded the Greek sovereign rating to Ba3 from Ba1. The sovereign’s credit rating (junk across agencies) relative to the other countries is given in the table below and is indicative of the yield pick-up of Greek debt.

Greek Bond Payments in the Future

Although Greece’s debt is primarily in the form of ‘official creditors’ loans like supranationals, for bondholders, it is also important to see how Greece’s bond payments are going to shape up in the future. 2021 sees the highest repayments on Greek bonds by the government over the foreseeable future at ~€8bn followed by 2028. It is also important to understand that simply because Greek debt is not primarily in the form of bonds doesn’t mean that bondholders are any less exposed to risks. In 2015, when Greece defaulted on $1.7bn of IMF loans, Greek yields rose over 10% with defaults expected across the bond curve while eventually calming down over the months with austerity measures and a new bailout package. Despite the above, bondholders should be careful not to assume that bailouts would always come to their rescue.

So Is Greece Over the Worst?

For now it appears that Greece has done a fair job after the chaos it suffered post the financial crisis. Greek 10Y yields have fallen from over double digit levels to less than 1% in the last 5 years, compared to the other peripheral yields which have moved from over 2% to less than 1%.

The Greek economy had been growing just over 0.1% QoQ and 1% YoY pre-Covid19. The pandemic has grossly hit growth across all countries with the economies of Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain down over 14%. Greece is particularly impacted by a hit to tourism as tourism accounts for ~18% of GDP and 20% of employment. Other structural problems including high unemployment rates also exist in Greece. While the fiscal deficit is set to hit 7% of GDP this year due to the pandemic, it has been contained over the last few years to less than 2% of GDP.

Though all isn’t perfect, central bank support, hopeful credit rating upgrades following that of Moody’s and a much improved state of affairs from the last 5-10 years bodes well for Greece at the moment – that is what bond markets also seem to indicate!

Go back to Latest bond Market News

Related Posts: